The POW Story.

Why it is so important to remember the struggles and sacrifices of the Prisoners of War of the Vietnam War.

You are not forgotten.

If you look at just about any flagpole in America, you will see the POW/MIA flag flying with the American flag. Since 1973, American citizens have used this symbol to honor those who suffered through years of captivity and torture and those who never came home. The words “You are not forgotten” are a constant reminder that we should always remember the sacrifices of these veterans who paid so dearly in the defense of freedom and our nation.

The American Heritage Museum constructed a lasting tribute to the POWs of the Vietnam War through the Hanoi Hilton Exhibit at the American Heritage Museum. Through the pages of this website you will learn how the original materials of several cells of the original Hỏa Lò prison in Hanoi, known by many as the “Hanoi Hilton” made their way to the United States (see “The Journey”) and were reconstructed as a core artifact within an immersive exhibit in the Vietnam War Gallery of the museum (see “The Project”). Though we accomplished this ambitious project on February 12, 2023, the 50th Anniversary of Operation Homecoming and the return of the POWs from Vietnam in 1973, we still need your support to complete the funding for the project as we still have a significant gap. Learn more about contributing in “We Need Your Help”.

The Hanoi Hilton.

Coined the “Hanoi Hilton” by American prisoner Robert Shumaker, the Hỏa Lò prison became synonymous with the POW plight during the War, and long after. American prisoners of war in the Hỏa Lò prison were subjected to extreme torture and malnutrition during their captivity. Although a signatory of the Third Geneva Convention of 1949, which demanded “decent and humane treatment” of prisoners of war, North Vietnam employed severe torture methods, including sleep deprivation, malnutrition, beatings, hanging by ropes, locking in irons, and prolonged solitary confinement.

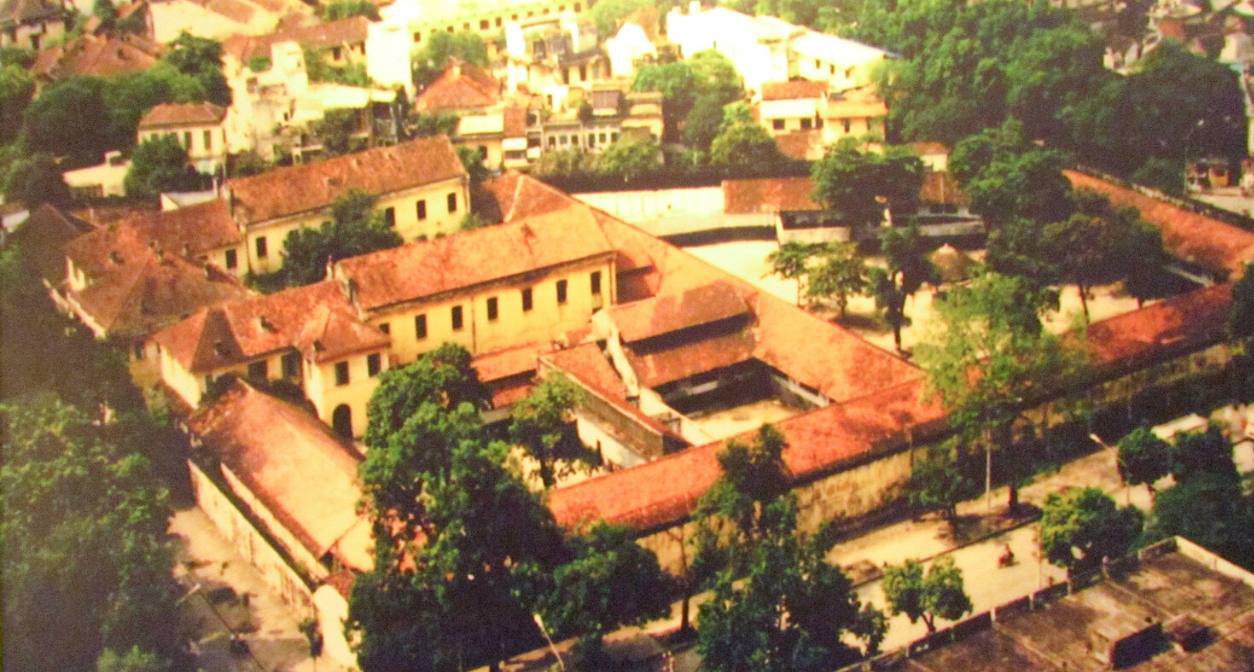

The prison was built in Hanoi by the French between 1886 to 1901, when Vietnam was still part of French Indochina. The French called the prison Maison Centrale or Central House, which is still the designation for prisons housing dangerous or long sentence detainees in France. Known locally as Hỏa Lò prison, it was built at the previous location of the Phu Khanh village. The village baked locally sourced earthenware in furnaces, and the name “Hỏa Lò” means “fiery furnace” or “stove.”

The prison was originally designed to house 460 inmates, but was often overcrowded. Due to the harsh nature of French rule and a vicious justice system, the prison was always oversupplied with inmates. Many were political prisoners agitating for independence who became the subjects of torture and execution.

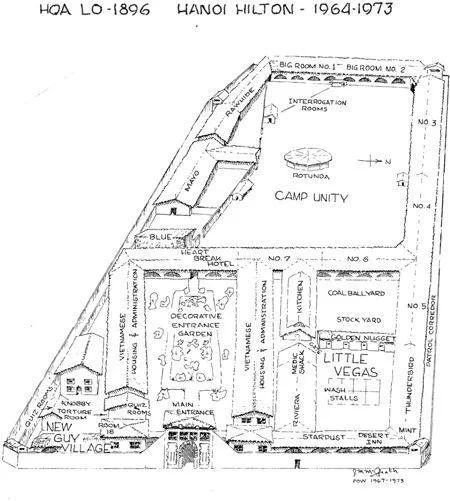

Re-purposed during the Vietnam War, the first U.S. prisoner sent to Hỏa Lò was Lieutenant Junior Grade Everett Alvarez Jr., who was shot down on August 5, 1964. From the beginning, U.S. POWs at Hỏa Lò endured miserable, unsanitary conditions, including meager rations of food and the ever-present threat starvation. Beginning early in 1967, a new area of the prison was opened for incoming American POWs. It was dubbed “Little Vegas,” and its individual buildings and areas were named after Las Vegas strip landmarks, such as “Golden Nugget,” “Thunderbird,” “Stardust,” “Riviera,” “Heartbreak Hotel” and the “Desert Inn.”

A hand drawn map reproduced from memory by POW Mike McGrath after release.

POWs not only endured terrible living conditions and isolation, but also repeated torture and abuse from guards.

A “tap code” of knocks and a “deaf mute” code of hand signals were the only ways POWs could communicate.

Hundreds of American POW’s, mostly airmen, endured months of isolation and squalid conditions at Hỏa Lò. POWs were repeatedly interrogated and tortured at the hands of their captors and endured enormous levels of physical and mental abuse. The North Vietnamese guards strictly enforced no communication within the prison, but POWs found ways to communicate including a tap code that could be heard through walls from one cell to another and a “Deaf Mute” code of hand signals that could be used when guards were not looking. Even with this limited communication, prisoners developed a code within their ranks to look out for and protect each other in whatever way they were able.

Several well-known veterans spent years in confinement there, including John McCain, James Stockdale, Bud Day, Joseph Kittinger, James Robinson Risner, Jerry Coffee, and Everett Alvarez. John McCain was tortured regularly for over five years, as was Bud Day. Navy pilot Everett Alvarez was interned in the Hanoi Hilton from August 1964 until February 1973, removed from the world for nearly a decade. He went in six months after The Beatles first visited the U.S. and was released three years after they broke up. Alvarez missed the entire British invasion, man walking on the moon and the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert Kennedy because he, and his fellow prisoners, had no news of the outside world.

On January 27, 1973, the Vietnam War ended for the United States as a withdrawal agreement of American troops out of South Vietnam was signed. The agreement included the negotiated release of the nearly 600 prisoners of war being held by North Vietnam in various prisons and camps including the Hanoi Hilton. The deal would come to be known as Operation Homecoming and began with three C-141 transports landing in Hanoi on February 12, 1973 to bring the first released prisoners home. From February 12th to April 4th, 54 flights took place, returning 591 POWs home.